The Quality of Life

Étonnant !

Ces gens boivent le café

dans des gobelets en carton

Baissent-ils encore leur

pantalon pour chier ?

(En Irak, ils n’ont même pas

le temps)

|

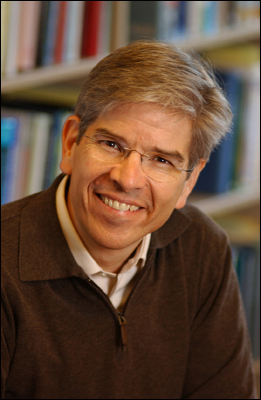

http://econo.free.fr/scripts/notes2.php3?codenote=158 http://www.reason.com/news/show/28243.html Post-Scarcity Prophet

Economist Paul Romer on growth, technological

change, and an unlimited human future. “One of the 25 most influential Americans,”

pronounced Time. “His ideas may just revolutionize the study of economics.”

Newsweek included him in its roster of “The Century Club,” a “list of

100 people for the New Century.” He is a perennial short-lister for the

Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. His work has been lauded by business guru

Peter Drucker and Nobel-winning economist Robert Solow. He is the STANCO 25

Professor of Economics at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Business

and a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution. He was recently elected a

fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. As one of the chief architects of “New Growth

Theory,” Paul Romer has had a massive and profound impact on modern economic

thinking and policymaking. New Growth Theory shows that economic growth

doesn’t arise just from adding more labor to more capital, but from new and

better ideas expressed as technological progress. Along the way, it

transforms economics from a “dismal science” that describes a world of

scarcity and diminishing returns into a discipline that reveals a path toward

constant improvement and unlimited potential. Ideas, in Romer’s formulation,

really do have consequences. Big ones. Before New Growth Theory, economists recognized

that technology contributed substantially to growth, but they couldn’t figure

out how to incorporate that insight into economic theory. Romer’s innovation,

expressed in technical articles with titles such as “Increasing Returns and

Long-Run Growth” and “Endogenous Technological Change,” has been to find ways

to describe rigorously and exactly how technological progress brings about

economic growth. As Robert Solow told Wired in 1996, “Paul single-handedly

turned [the study of economic growth] into a hot subject.” The 46-year-old Romer, son of former Colorado Gov.

Roy Romer, received his Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago in

1983, six years after earning a B.S. in physics at the same school. Before

joining Stanford’s faculty in 1996, he taught at a number of schools,

including the University of Chicago, the University of Rochester, and the

University of California at Berkeley. He and his wife, Virginia Langmuir, a

medical doctor, live in Portola Valley, California, and have two children. In June, reason Science Correspondent Ronald

Bailey interviewed Romer poolside at his house, which overlooks a huge

expanse of rolling ranchland owned by Stanford University. For more

information on Romer’s theories, turn to his Web site, www.stanford.edu/~promer/index.html. * * * reason: In terms of real per

capita income, Americans today are seven times richer than they were in 1900.

How did that happen? Paul Romer: Many things contributed,

but the essential one is technological change. What I mean by that is the

discovery of better ways to do things. In most coffee shops these days, you’ll find that the

small, medium, and large coffee cups all use the same size lid now, whereas

even five years ago they used to have different size lids for the different

cups. That small change in the geometry of the cups means that

somebody can save a little time in setting up the coffee shop, preparing the

cups, getting your coffee, and getting out. Millions of little discoveries

like that, combined with some very big discoveries, like the electric motor

and antibiotics, have made the

quality of life for people today dramatically higher than it was 100

years ago. The estimate you cite of a seven-fold increase in

income — that’s the kind of number you get from the official statistics, but

the truth is that if you look at the actual change in the quality of life,

it’s larger than the number suggests. People who had today’s average income

in 1900 were not as well off {aisés}

as the average person today, because they didn’t have access to cheap lattés {the stereotypical yuppie drink

(Wikipédia). Le “e” accentué est une frenchization de l’italien latte par certains américains alors que les français

écrivent latte et prononcent latté. En français, latté désigne le bois latté-collé. Le

laté est aussi une boisson d’Amérique du sud, me semble-t-il} or antibiotics or penicillin {Dr Destouche :

avant la pénicilline, la médecine ne guérissait rien}. reason: New Growth Theory divides

the world into “ideas” and “things.” What do you mean by that? Romer: The paper that

makes up the cup in the coffee shop is a thing. The

insight that you could design small, medium, and large cups so that they all

use the same size lid — that’s an idea. The critical difference is that only one person can use

a given amount of paper. Ideas can be used by many people at the same time. reason: What about human capital, the

acquired skills and learned abilities that can increase productivity? Romer: Human capital is

comparable to a thing. You have skills as a

writer, for example, and somebody — reason — can use those skills. That’s not

something that we can clone and replicate. The formula for an AIDS drug,

that’s something you could send over the Internet

or put on paper,

and then everybody in the world could have access to it. This is a hard distinction for people to get used

to, because there are so many tight interactions between human capital and

ideas. For example, human capital is how we make ideas. It takes people,

people’s brains, inquisitive people, to go out and find ideas like new drugs

for AIDS. Similarly, when

we make human capital with kids in school, we use ideas like the

Pythagorean theorem or the quadratic formula. So human capital makes ideas,

and ideas help make human capital. But still, they’re conceptually distinct. reason: What do you see as the

necessary preconditions for technological progress and economic growth? Romer: One extremely important

insight is that the process of technological discovery is supported by a

unique set of institutions. Those are most productive when they’re tightly

coupled with the institutions of the market. The Soviet Union had very strong

science in some fields, but it wasn’t coupled with strong institutions in the

market. The upshot was that the benefits of discovery were very limited for

people living there. The

wonder of the United States is that we’ve created institutions of

science and institutions of the market. They’re very different, but together

they’ve generated fantastic benefits. When we speak of institutions, economists mean

more than just organizations. We mean conventions, even rules, about how things are done.

The understanding which most sharply distinguishes science from the market

has to do with property rights. In the market, the fundamental institution is

the notion of private ownership, that an individual owns a piece of land or a

body of water or a barrel of oil and that individual has almost unlimited

scope to decide how that resource should be used. In science we have a very different ethic. When

somebody discovers something like the quadratic formula or the Pythagorean

theorem, the convention

in science is that he can’t control that idea. He has to give it away. He

publishes it. What’s rewarded in science is dissemination of ideas. And the

way we reward it is we give the most prestige and respect to those people who

first publish an idea. reason: Yet there is a mechanism

in the market called patents and copyright, for quasi-property rights in

ideas. Romer: That’s central to the

theory. To the extent that you’re using the market system to refine and bring

ideas into practical

application, we have to create some kind of control over the idea.

That could be through patents. It could be through copyright. It might even

be through secrecy. A firm can keep secret a lot of what it knows how to do. reason: A formula for Coca-Cola? Romer: Yes. Or take a lot of the

things that Wal-Mart understands about discount retailing. They have a lot of

insight about logistics and marketing which they haven’t patented or

copyrighted, yet they can still make more money on it than other people

because they keep it closely held within the firm. So for relying on the

market — and we do have to rely on the market to develop a lot of ideas — you

have to have some mechanisms of control and some opportunities for people to

make a profit developing those ideas. But there are other stages in the development of

ideas. Think about the basic science that led to the discovery of the

structure of DNA. There are some kinds of ideas where, once those ideas are

uncovered, you’d like to make them as broadly available as possible, so

everybody in the world can put them to good use. There we find it efficient

to give those ideas away for free and encourage everybody to use them. If

you’re going to be giving things away for free, you’re going to have to find

some system to finance them, and that’s where government support typically comes in. In the next century we’re going to be moving back

and forth, experimenting with where to draw the line between institutions of

science and institutions of the market. People used to assign different types

of problems to each institution. “Basic research” got government support; for

“applied product development,” we’d rely on the market. Over time, people

have recognized that that’s a pretty artificial distinction. What’s becoming

more clear is that it’s actually the combined energies of those two sets of

institutions, often working on the same problem, that lead to the best

outcomes. reason: We hear a lot of

complaints from academicians about how business and corporations are taking

over university research. Romer: I think it’s important to

have a distinct realm of science and a distinct realm of the market, but it’s

also very good to have interaction between those two. One of the best forms

of interaction is for people who work in one to move into the other. The people in university biology or biochemistry

departments complain when they see somebody go on leave from the university

and start a company that’s going to develop a new drug. That’s not the way it

was done 30 years ago. But this is the best way to take those freely

floating, contentiously discussed ideas from the realm of science and then

get them out into the market process, because the reality is that there are virtually

no ideas which generate

benefits for consumers if there’s not an intervening for-profit firm

which commercializes them, tailors them to the market, and then delivers

them. You can point to examples where things jump right from science to

benefits for the consumer, but that’s the exception, not the rule. reason: Do we run the risk of

ruining science by involving it too much in the market? Romer: Well, some people would

say that everything should be patented. The danger is that if you went that

far, you could actually slow the discovery process down. There are very good

theoretical reasons for thinking that market and property rights are the

ideal solution for dealing

with things, but there are also strong theoretical reasons for

thinking that in the realm of ideas, intellectual property rights are a

double-edged sword. You want to rely on them to some extent to get their

benefits, but you want to have a parallel, independent system and then

exploit the tension that’s created between the two. reason: What are those

theoretical reasons? Romer: It traces back to this

multiple use I was describing for ideas vs. single use for things. The miracle of the market system is that

for objects, especially transformed objects, there’s a single price which does two different jobs.

It creates an incentive for somebody to produce the right amount of a good,

and it allocates who it should go to. A farmer looks at the price of a bushel

of wheat and decides whether to plant wheat or plant corn. The price helps

motivate the production of wheat. On the other side, when a consumer has to

decide whether to buy bread or corn meal, the price allocates the wheat

between the different possible users. One price does both jobs, so you can just let the market

system create the price and everything works wonderfully. With ideas, you can’t get one price to do both

things. Let me give an extreme example. Oral rehydration therapy is one of

those few ideas which did actually jump immediately from science to consumer

benefit. It’s a simple scientific insight about how you can save the life of

a child who’s suffering from diarrhea. Literally millions of lives have been

saved with it. So what price should you charge people for using it? Because everybody can use the idea at the same

time, there’s no tragedy of the commons {droits

au sens de copyright, avoir le droit de} in the intellectual

sphere. There’s no problem of overuse or overgrazing or overfishing an idea.

If you give an idea away for free, you don’t get any of the problems when you

try and give objects away for free. So the efficient thing for society is to

offer really big rewards for some scientist who discovers an oral rehydration

therapy. But then as soon as we discover it, we give the idea away for free

to everybody throughout the world and explain “Just use this little mixture

of basically sugar and salt, put it in water, and feed that to a kid who’s

got diarrhea because if you give them pure water you’ll kill them.” So with

ideas, you have this tension: You want high prices to motivate discovery, but

you want low prices to achieve efficient widespread use. You can’t with a

single price achieve both, so if you push things into the market, you try to

compromise between those two, and it’s often an unhappy compromise. The government doesn’t pay drug companies prizes

for coming up with AIDS drugs. It says they’ve got to incur {supporter, engager} these huge expenses,

but then if they succeed, they can charge a high price for selling that drug.

This has generated a lot of progress and we’re prolonging the life of people

with AIDS, but the high price is also denying many people access to those

drugs. reason: Over the broad sweep of

human history, technological progress and economic growth were painfully

slow. Why has it sped up now? Romer: It’s so striking.

Evolution has not made us any smarter in the last 100,000 years. Why for

almost all of that time is there nothing going on, and then in the last 200

years things suddenly just

go nuts? One answer

is that the more people you’re around, the better off {à

l’aise, aisé, riche, I suppose. Plus on est de fous, plus on rit}

you’re going to be. This again traces back to the fundamental difference I

described before. If everything were just objects, like trees, then more people means there’s

less wood per person. But if somebody discovers an idea, everybody gets to use it, so the more

people you have who are potentially looking for ideas, the better off we’re

all going to be. And each time we made a little improvement in technology, we

could support a slightly larger population, and that led to more people who

could go out and discover some new technology. Another answer is that we developed better

institutions. Neither the

institutions of the market nor the institutions of science existed even as late

as the Middle Ages. Instead we had the feudal system, where peasants couldn’t

decide where to work and the lord couldn’t sell his land. On the science

side, we had alchemy. What did you do if you discovered anything? You kept it

secret. The last thing you’d do was tell anybody. reason: How did the better

institutions come about? Romer: That’s one of the deep

questions. There’s some kind of political process, some group decision

process, which leads to institutions. If you go back to what I said a minute

ago about the advantages of having many people, you can see that there’s a

tension here. There are huge benefits to having more people and having us all

interact amongst ourselves to

create goods and to share ideas. But you face a really big challenge

in trying to coordinate all of those decisions, because if you have large

numbers of independent decision makers who aren’t coordinating their actions

appropriately, you could get chaos. Think about millions of drivers with no rules of the road,

no agreement about whether you drive on the left or the right. So where do these institutions come from? It was a

process of discovery,

just as people discovered how to make bronze. They also discovered ways to

organize political life {naïf salaud}.

We can use democratic choice as an alternative to, say, a hereditary system

of selecting who’s the king. What’s subtle here is, How do those discoveries

get into action? It’s not like a profit motive in a firm that brings software to market.

There was a process of persuasion when somebody discovered that, hey, this

would be a better way for us to organize ourselves. So we had political and

economic thinkers — Locke, Hobbes, Smith — who managed to persuade some of

their peers to adopt those institutions. So institutions came from a combination of

discovery, persuasion, adoption — and then copying. When good institutions

work somewhere in the world, other places can copy them. reason: Many economic historians are

critical of New Growth Theory. Economic growth is a modern phenomenon, yet it

appears that New Growth Theory should apply equally to the Roman Empire or

Ming China as well as the modern world. Romer: I think that’s a

caricature of the theory. New Growth Theory describes what’s possible for us

but says very explicitly that if you don’t have the right institutions in

place, it won’t happen. If anything, it was the old style of theory which

made it sound like technological change falls from the sky like manna from

heaven, regardless of how we structure our institutions. This new theory says

technological change comes about if you have the right institutions, which we

have had. reason: So what’s the crucial

difference between Ming China and modern economies today? Romer: Ming China was very

advanced. It had steel. It had clocks. It had movable type. Yet it was far

from generating either the

modern institutions of science or the institutions of the market. The market and science differ in their treatment

of property rights, but they’re similar in that they rely on individuals who

are free to operate under essentially no constraints by authority or

tradition. It took a special set of historical circumstances to persuade

people that things could work if you freed people, within certain

institutional constraints, to pursue their own interests. This is where Ming

China was very far away from modern notions. Part of the answer to this big question about

human history has been the acceptance of relatively unfettered {sans entraves. Fettered, enchaîné}

freedom for large numbers of individuals. It’s something we just take for

granted, but if you described it in the abstract to the people of 50,000

years ago, they would never believe it could possibly work. They were conditioned

to systems where there was the head man or the chief, and as numbers got at

all large, there was a sense that you had to have somebody with kind of

dictatorial control. It was a deep philosophical insight and deep change in

the whole way we viewed the world to tolerate and accept and then truly

celebrate freedom. Freedom

may be the fundamental hinge {gond, pivot}

on which everything turns. reason: You often cite the

combinatorial explosion of ideas as the source of economic growth. What do

you mean by that? Romer: On any conceivable

horizon — I’ll say until about 5 billion years from now, when the sun

explodes — we’re not going to run out of discoveries. Just ask how many

things we could make by taking the elements from the periodic table and

mixing them together. There’s a simple mathematical calculation: It’s 10

followed by 30 zeros. In contrast, 10 followed by 19 zeros is about how much

time has elapsed since the universe was created. reason: Of all those billions of

combinations, the vast majority are probably going to be useless. So how do

you find the useful ones? Romer: This is why science and the market are so

important for this discovery process. It’s really important that we focus

our energy on those paths that look promising, because there are many more

dead ends out there than there are useful things to discover. You have to have systems which explore lots of

different paths, but then those systems have to rigorously shut off the ones

that aren’t paying off

and shift resources into directions which look more promising. The market does this

automatically. The institutions of science could tip either way. In

American science, we have vigorous competition between lots of different

universities, which leads to a kind of marketplace of ideas. You can think of

other institutions of science that aren’t nearly as competitive. In the

national laboratories, people are in the worst case civil servants: They’re

there for life, and there’s always more funding for them. reason: Does New Growth Theory

give us some new insights on how to think about monopolies? Romer: There was an old,

simplistic notion that monopoly was always bad. It was based on the realm of

objects — if you only have objects and you see somebody whose cost is

significantly lower than their price, it would be a good idea to break up the

monopoly and get competition to reign freely. So in the realm of things, of

physical objects, there is a theoretical justification for why you should

never tolerate monopoly. But in the realm of ideas, you have to have some

degree of monopoly power. There are some very important benefits from

monopoly, and there are some potential costs as well. What you have to do is

weigh the costs against the benefits. Unfortunately, that kind of balancing test is

sensitive to the specifics, so we don’t have general rules. Compare the costs

and benefits of copyrighting books versus the costs and benefits of patenting

the human genome. They’re just very different, so we have to create

institutions that can respond differentially in those cases. reason: You have written, “There

is absolutely no reason why we cannot have persistent growth as far into the

future as you can imagine.” Your Stanford colleague, the biologist Paul

Ehrlich, disagrees. He believes that economic growth is an unsustainable

cancer that is destroying the planet. How would you go about convincing

people like Ehrlich that they are wrong? Romer: Paul seems singularly

immune to being convinced. He has been on the wrong side of these issues, so

I wouldn’t set that as my standard of persuading anybody. However, if I took

a neutral observer who might listen to me and Paul, there’s a pretty easy way

to explain why I’m right and why Paul misunderstands. You have to define what

you mean by growth. If by growth you mean population, more people, then Paul

is actually right. There are physical limits on how many people you can have

on Earth. If we took peak population growth rates from the ‘70s at 2 percent

per year, you can only sustain that for a couple of hundred years before you

really run into true physical constraints. reason: I would remind you that

Ehrlich said that there would be billions of people dying of starvation in

the 1980s. Romer: He got the potentials

wrong and the time frame wrong, but it’s absolutely true that population

growth will have to come to zero at some point here on Earth. The only debate

is about when. Now, what do I mean when I say growth can

continue? I don’t mean growth in the number of people. I don’t even mean

growth in the number of physical objects, because you clearly can’t get

exponential growth in the amount of mass that each person controls. We’ve got

the same mass here on Earth that we had 100,000 years ago and we’re never

going to get any more of it. What I mean is growth in value, and the way you

create value is by taking that fixed quantity of mass and rearranging it from

a form that isn’t worth very much into a form that’s worth much more. A canonical example is turning

sand on the beach into semiconductors. reason: What do you make of the

recent protests against globalization? Romer: When we were describing

the broad sweep of human history, we talked about how hard it was for people

to get used to the idea

of freedom. There was another kind of adjustment that we had to make

as well: We had to get used to the idea of the market, and especially market exchange among

anonymous strangers. People often contrast this with the institutions of the

family, where you’ve got notions of sharing and mutual obligation. Many of us

have a deep psychological intuition rooted in our evolutionary history that

makes us feel warmly toward the family and suspicious of large, impersonal,

anonymous market exchange. I think that emotional impulse is part of what

some of the environmental ideologues draw on when they attack the whole

market system and corporations and modern science and everything. This is a case where human psychology that was

attuned to a hunter-gatherer environment is just a little bit out of touch

with a new world that’s much more interconnected, much more interactive, and

in many ways a much more satisfying and rich human experience. You can

idealize life in a hunter-gatherer society {mais

celle des Etats-Unis, vous pouvez aussi, c’est même recommandé si j’en juge

par l’interviewé}, but nobody wants to go through the frequent death

of a child — a very common experience for almost all of history that has been

reduced a phenomenal degree within human memory. reason: How would you convince

protestors of the benefits of globalization? Romer: First, just look at the facts. The protestors are amazingly ignorant

about what has happened in terms of, say, life expectancy. Life expectancy for people in

the poorest countries of the world is now better than life expectancy in

England when Malthus was so worried about it ♦.

Then you look at the variation of experience

between the poor countries that have done best and the ones that have done

worst, and try to see what the correlations are. Which countries did best?

Was it the countries that adopted the market most strongly, embraced foreign

investment, and tried to adopt property rights? Or was it the other countries? The evidence again is clear. One of the untold

stories about the ‘80s and ‘90s was the really dramatic turnaround in the developing

world that took place on this issue. If you track the legislative history on

foreign investment, you see a colonial legacy, even as late as the ‘70s,

where developing countries have laws designed to keep corporations out. Then

there’s this dramatic turnaround as they saw the benefits that a few key

economies received by inviting in foreign investment. It’s not the people

from the developing world who are making the argument that Nike is a threat

to their sovereignty or well-being. It’s people in the United States. The

people in the developing world understand pretty clearly where their

self-interest lies. reason: What about boosting

economic growth in developed countries? Romer: For Europe and the United

States, I think we need to be thinking very hard about how we can restructure

our institutions of science. How can we restructure our system of higher

education? How can we make sure that it has the benefits of vigorous

competition and free entry, especially of those bright young people who might

do really different kinds of things? We should not assume that we’ve already

got the ideal institutions and the only thing we need to do is just throw

more money at them. Unfortunately, I think a lot of countries have a

long way to go to catch up to the state where we are in the United States —

and I’m not that happy about where we are in the United States. Many European

countries simply have not recognized the power of competition between

institutions. So they have monolithic, state-run university systems. That

stifles competition between individual researchers and slows down the whole

innovative process. They also need to let people move more flexibly from the

university into the private sector and back. This is something that many

countries watching venture capital start-ups have become aware of, although

they’ve been slower to get their institutions to adjust. reason: In your recent paper on

doing R&D, you said you think it would be possible to raise the growth

rate from its average rate of 1.8 percent between 1870 and 1992 to 2.3

percent. Romer: Well, I was trying to set

a goal. When you’re thinking about the future, you never really know what

we’re going to discover, but I think there’s a reason to set for ourselves an

ambition of trying to raise the rate of growth by half a percent per year.

The United States achieved about 0.5 percent a year faster growth than the

U.K. did since 1870, so we’ve got a historical precedent for creating

institutions which lead to better innovation of the market and strengthen

science significantly. We should aim for that kind of improvement again. reason: Why would that be

important? Romer: As you accumulate these

growth rates over the decades, we get much higher levels of income. That lets

us deal more effectively with all the problems we face, whether it’s making

good on commitments to pay for people’s health care as they get older,

preserving more of the environment, or providing resources so that people can

have time to be out of the labor market for a certain period of time — when

they’re raising kids, say, or when they want to take an extended sabbatical. Income per capita in 2000 was about $36,000 in

year 2000 dollars. If real income per person grows at 1.8 percent per year,

by 2050 it will increase to $88,000 in year 2000 purchasing power. Not bad.

But if it grows at 2.3 percent per year, it will grow to about $113,000 in

year 2000 purchasing power. In today’s purchasing power, that extra $25,000

per person is equal to income per capita in 1984. So if we can make the choices

that increase the rate of growth or real income per person to 2.3 percent per

year, in 50 years we can get extra income per person equal to what in 1984 it

had taken us all of human history to achieve. One policy innovation, for example, that would boost

the growth rate would be to subsidize universities to train more

undergraduate and graduate students in science and engineering. Also, you

could give graduate students portable fellowships that they could use to pay

for training in any field of natural science and engineering at any

institution the students choose. Graduate students would no longer be hostage

to the sometimes parochial research interests of university professors.

Portable fellowships would encourage lab directors and professors to develop

programs that meet the research and career interests of the students. reason: What’s next in New Growth

Theory? Any conceptual breakthroughs on the horizon? Romer: Because the economics of

ideas are so different from the economics of markets, we’re going to have to

develop a richer understanding of non-market institutions, science-like

institutions. This is going to be a new endeavor for economics. reason: Do you think that there

is a big role for economic historians in helping uncover this richer theory? Romer: History is an absolutely

essential body of evidence, because you can’t make inferences about long-run

trends using year-to-year or quarter-to-quarter data. reason: There is a growing

movement against technological progress around the world. Why is there this

negative reaction to technological progress and what can we do about it? Romer: You’re a big believer in

turmoil and creative destruction when you’re early in life, because you can

knock down the old and create your new thing. Once you achieve a certain

level, you tend to get very conservative and try to slow the gales down,

because they might blow you over. So I think we have to seriously commit

ourselves to maintaining space for new entrants and for young people. That’s

one way to keep the process going. Another is to do what scholars have always

done: to proselytize, to dissect incoherent arguments. I think we’ll be able to maintain this dynamic of

progress that was unleashed a couple centuries ago. There will be small

setbacks and a lot of noise and complaining, but the opportunities and the

benefits are just too great to pull back. reason: Could anything stop

economic growth and technological progress? Romer: Even if one society loses

its nerve, there’ll be new entrants who can take up the torch and push ahead.

Mancur Olson talks about Caldwell’s Law, the idea that no nation has remained

truly innovative for very long. Look at Italy, and then Holland, and then the

U.K., and then the United States. The pessimistic interpretation is that nobody

can keep the process going. The optimistic interpretation is, Yes, you can,

but somebody else comes along and the progress moves from one place to the

next. We’ve seen individual societies where conservative

or reactionary elements suppress the changes. What has protected us in the

past is that there were other nations that could try new paths. You didn’t

have the same political dynamic everywhere at once. If in the far future we reach a situation where

there really is truly global political control — if multinational

institutions grow more powerful over economic affairs so that there is

imposed uniformity across all nations — then there’d be a loss of diversity.

And if the reactionary elements got in control of those institutions, there’d

be no room for the new entrant, the upstart, to adopt new ideas. But that’s a

pretty distant and unlikely prospect. |